Part 1: Creating your first Application Package¶

All tutorials on programming languages start with a “Hello, World” example, and since Murano provides its own programming language, this guide will start the same way. Let’s do a “Hello, World” application. It will not do anything useful yet, but will provide you with an understanding of how things work in Murano. We will add more logic to the package at later stages. Now let’s start with the basics:

Creating package manifest¶

Let’s start with creating an empty Murano Package. All packages consist of multiple files (two at least) organized into a special structure. So, let’s create a directory somewhere in our file system and set it as our current working directory. This directory will contain our package:

$ mkdir HelloWorld

$ cd HelloWorld

The main element of the package is its manifest. It is a description of the

package, telling Murano how to display the package in the catalog. It is

defined in a yaml file called manifest.yaml which should be placed right in

the main package directory. Let’s create this file and open it with any text

editor:

$ vim manifest.yaml

This file may contain a number of sections (we will take a closer look at some

of them later), but the mandatory ones are FullName and Type.

The FullName should be a unique identifier of the package, the name which

Murano uses to distinguish it among other packages in the catalog. It is very

important for this name to be globally unique: if you publish your package and

someone adds it to their catalog, there should be no chances that someone

else’s package has the same name. That’s why it is recommended to give your

packages Full Names based on the domain you (or the company your work for) own.

We recommend using “reversed-domain-name” notation, similar to the one used in

the world of Java development: if the yourdomain.com is the domain name you

own, then you could name your package com.yourdomain.HellWorld. This way

your package name will not duplicate anybody else’s, even if they also named

their package “HelloWorld”, because theirs will begin with a different

domain-specific prefix.

Type may have either of two values: Application or Library.

Application indicates the standard package to deploy an application with

Murano, while a Library is bundle of reusable scenarios which may be used

by other packages. For now we just need a single standalone app, so let’s

choose an Application type.

Enter these values and save the file. You should have something like this:

FullName: com.yourdomain.HelloWorld

Type: Application

This is the minimum required to start. We’ll add more manifest data later.

Adding a class¶

While manifests describe Murano packages in the catalog, the actual logic of

packages is put into classes, which are plain YAML files placed into the

Classes directory of the application package. So, let’s create a directory

to store the logic of our application, then create and edit the file to contain

the first class of the package.

$ mkdir Classes

$ vim Classes/HelloWorld.yaml

Murano classes follow standard patterns of object-oriented programming: they define the types of the objects which may be instantiated by Murano. The types are composed of properties, defining the data structure of objects, and methods, containing the logic that defines the way in which Murano executes the former. The types may be extended: the extended class contains all the methods and properties of the class it extends, or it may override some of them.

Let’s type in the following YAML to create our first class:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | Name: com.yourdomain.HelloWorld

Extends: io.murano.Application

Methods:

deploy:

Body:

- $reporter: $this.find('io.murano.Environment').reporter

- $reporter.report($this, "Hello, World!")

|

Let’s walk through this code line by line and see what this code does.

The first line is pretty obvious: it states the name of our class,

com.yourdomain.HelloWorld. Note that this name matches the name of the

package - that’s intentional. Although it is not mandatory, it is strongly

recommended to give the main class of your application package the same name as

the package itself.

Then, there is an Extends directive. It says that our class extends (or

inherits) another class, called io.murano.Application. That is the base

class for all classes which should deploy Applications in Murano. As many other

classes it is shipped with Murano itself, thus its name starts with

io.murano. prefix: murano.io domain is controlled by the Murano development

team and no one else should create packages or classes having names in that

namespace.

Note that Extends directive may contain not only a single value, but a

list. In that case the class we create will inherit multiple base classes.

Yes, Murano has multiple inheritance, yay!

Now, the Methods block contains all the logic encapsulated in our class. In

this example there is just one method, called deploy. This method is

defined in the base class we’ve just inherited - the io.murano.Application,

so here we override it. Body block of the method contains the

implementation, the actual logic of the method. It’s a list of instructions

(note the dash-prefixed lines - that’s how YAML defines lists), each executed

one by one.

There are two instruction statements here. The first one declares a variable

named $reporter (note the $ character: all the words prefixed with it

are variables in Murano language) and assigns it a value. Unlike other

languages Murano uses colon (:) as an assignment operator: this makes it

convenient to express Murano statements as regular YAML mappings.

The expression to the right of the colon is executed and the result value is

assigned to a variable to the left of the colon.

Let’s take a closer look at the right-hand side of the expression in the first statement:

- $reporter: $this.find('io.murano.Environment').reporter

It takes a value of a special variable called $this (which always contains

a reference to the current object, i.e. the instance of our class for which the

method was called; it is same as self in python or this in Java) and

calls a method named find on it with a string parameter equal

to ‘io.murano.Environment’; from the call result it takes a “reporter”

attribute; this value is assigned to the variable in the left-hand side of the

expression.

The meaning of this code is simple: it finds the object of class

io.murano.Environment which owns the current application and returns its

“reporter” object. This io.murano.Environment is a special object which

groups multiple deployed applications. When the end-user interacts with Murano

they create these Environments and place applications into them. So, every

Application is able to get a reference to this object by calling find

method like we just did. Meanwhile, the io.murano.Environment class has

various methods to interact with the “outer world”, for example to report

various messages to the end-user via the deployment log: this is done by the

“reporter” property of that class.

So, our first statement just retrieved that reporter. The second one uses it to display a message to a user: it calls a method “report”, passes the reference to a reporting object and a message as the arguments of the method:

- $reporter.report($this, "Hello, World!")

Note that the second statement is not a YAML-mapping: it does not have a colon inside. That’s because this statement just makes a method call, it does not need to remember the result.

That’s it: we’ve just made a class which greets the user with a traditional

“Hello, World!” message. Now we need to include this class into the package we

are creating. Although it is placed within a Classes subdirectory of the

package, it still needs to be explicitly added to the package. To do that, add

a Classes section to your manifest.yaml file. This should be a YAML

mapping, having class names as keys and relative paths of files within the

Classes directory as the values. So, for our example class it should look

like this:

Classes:

com.yourdomain.HelloWorld: HelloWorld.yaml

Paste this block anywhere in the manifest.yaml

Pack and upload your app¶

Our application is ready. It’s very simplistic and lacks many features required for real-world applications, but it already can be deployed into Murano and run there. To do that we need to pack it first. We use good old zip for it. That’s it: just zip everything inside your package directory into a zip archive, and you’ll get a ready-to-use Murano package:

$ zip -r hello_world.zip *

This will add all the contents of our package directory to a zip archive called

hello_world.zip. Do not forget the -r argument to include the files in

subdirectories (the class file in our case).

Now, let’s upload the package to murano. Ensure that your system has a murano-client installed and your OpenStack cloud credentials are exported as environmnet variables (if not, sourcing an openrc file, downloadable from your horizon dashboard will do the latter). Then execute the following command:

$ murano package-import ./hello_world.zip

Importing package com.yourdomain.HelloWorld

+----------------------------------+---------------------------+---------------------------+-----------+--------+-----------+-------------+---------+

| ID | Name | FQN | Author | Active | Is Public | Type | Version |

+----------------------------------+---------------------------+---------------------------+-----------+--------+-----------+-------------+---------+

| 251a409645d1444aa1ead8eaac451a1d | com.yourdomain.HelloWorld | com.yourdomain.HelloWorld | OpenStack | True | | Application | |

+----------------------------------+---------------------------+---------------------------+-----------+--------+-----------+-------------+---------+

As you can see from the output, the package has been uploaded to Murano catalog and is now available there. Let’s now deploy it.

Deploying your application¶

To deploy an application with Murano one needs to create an Environment and add configured instances of your applications into it. It may be done either with the help of user interface (but that requires some extra effort from package developer) or by providing an explicit JSON, describing the exact application instance and its configuration. Let’s do the latter option for now.

First, let’s create a json snippet for our application. Since the app is very basic, the snippet is simple as well:

[

{

"op": "add",

"path": "/-",

"value": {

"?": {

"name": "Demo",

"type": "com.yourdomain.HelloWorld",

"id": "42"

}

}

}

]

This json follows a standard json-patch notation, i.e. it defines a number of

operations to edit a large json document. This particular one adds (note the

value of op key) an object described in the value of the json to the

root (note the path equal to /- - that’s root) of our environment.

The object we add has the type of com.yourdomain.HelloWorld - that’s the

class we just created two steps ago. Other keys in this json parameterize the

object we create: they add a name and an id to the object. Id is mandatory,

name is optional. Note that since the id, name and type are the system

properties of our object, they are defined in a special section of the json -

the so-called ?-header. Non-system properties, if they existed, would be

defined at a top-level of the object. We’ll add them in a next chapter to see

how they work.

For now, save this JSON to some local file (say, input.json) and let’s

finally deploy the thing.

Execute the following sequence of commands:

$ murano environment-create TestHello

+----------------------------------+-----------+--------+---------------------+---------------------+

| ID | Name | Status | Created | Updated |

+----------------------------------+-----------+--------+---------------------+---------------------+

| 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c | TestHello | ready | 2016-10-04T13:19:12 | 2016-10-04T13:19:12 |

+----------------------------------+-----------+--------+---------------------+---------------------+

$ murano environment-session-create 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c

Created new session:

+----------+----------------------------------+

| Property | Value |

+----------+----------------------------------+

| id | 6d4a8fa2a5f4484fbc07740ef3ab60dd |

+----------+----------------------------------+

$ murano environment-apps-edit --session-id 6d4a8fa2a5f4484fbc07740ef3ab60dd 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c ./input.json

This first command creates a murano environment named TestHello. Note the

id of the created environment - we use it to reference it in subsequent

operations.

The second command creates a “configuration session” for this environment. Configuration sessions allow one to edit environments in transactional isolated manner. Note the id of the created sessions: all subsequent calls to modify or deploy the environment use both ids of environment and session.

The third command applies the json-patch we’ve created before to our environment within the configuration session we created.

Now, let’s deploy the changes we made:

$ murano environment-deploy --session-id 6d4a8fa2a5f4484fbc07740ef3ab60dd 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c

+------------------+---------------------------------------------+

| Property | Value |

+------------------+---------------------------------------------+

| acquired_by | 7b0fe7c67ede443da9840adb2d518d5c |

| created | 2016-10-04T13:39:34 |

| description_text | |

| id | 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c |

| name | TestHello |

| services | [ |

| | { |

| | "?": { |

| | "name": "Demo", |

| | "status": "deploying", |

| | "type": "com.yourdomain.HelloWorld", |

| | "id": "42" |

| | } |

| | } |

| | ] |

| status | deploying |

| tenant_id | 60b7b5f7d4e64ff0b1c5f047d694d7ca |

| updated | 2016-10-04T13:39:34 |

| version | 0 |

+------------------+---------------------------------------------+

This will deploy the environment. You may check for its status by executing the following command:

$ murano environment-show 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c

+------------------+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Property | Value |

+------------------+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| acquired_by | None |

| created | 2016-10-04T13:39:34 |

| description_text | |

| id | 34bf673a26a8439d906827dea328c99c |

| name | TestHello |

| services | [ |

| | { |

| | "?": { |

| | "status": "ready", |

| | "name": "Demo", |

| | "type": "com.yourdomain.HelloWorld/0.0.0@com.yourdomain.HelloWorld", |

| | "_actions": {}, |

| | "id": "42", |

| | "metadata": null |

| | } |

| | } |

| | ] |

| status | ready |

| tenant_id | 60b7b5f7d4e64ff0b1c5f047d694d7ca |

| updated | 2016-10-04T13:40:29 |

| version | 1 |

+------------------+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

As you can see, the status of the Environment has changed to ready: it

means that the application has been deployed. Open Murano Dashboard, navigate

to Environment list and browse the contents of the TestHello environment

there.

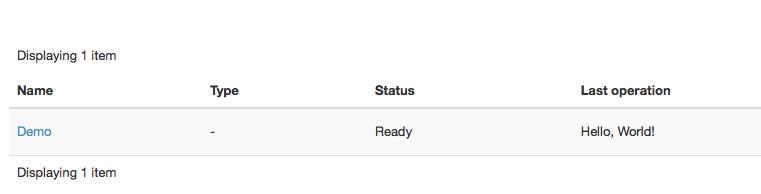

You’ll see that the ‘Last Operation’ column near the “Demo” component says

“Hello, World!” - that’s the reporting made by our application:

This concludes the first part of our course. We’ve created a Murano Application Package, added a manifest describing its contents, written a class which reports a “Hello, World” message, packed all of these into a package archive and uploaded it to Murano Catalog and finally deployed an Environment with this application added.

In the next part we will learn how to improve this application in various aspects, both from users’ and developers’ perspectives.

Except where otherwise noted, this document is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. See all OpenStack Legal Documents.